Iconic...

Forgotten...

Timeless...

Innovative...

These are the soundtracks that helped shape and define what we hear in the video games that we play. I am Nitro, and this is the M Disk Playlist's Video Game Music Primer: 1990.

Dragon Quest IV (Nintendo), composed by Koichi Sugiyama

Dragon Quest IV tells the story of a hero, and his companions who we learn about in separate chapters, in a quest to save the world from Psaro the Manslayer, who aspires to become the next Ruler of Evil. It would be hard to talk about video game primers without talking about the Dragon Quest series. Koichi Sugiyama, the one video game composer to be deisgnated as the oldest gaming composer by the Guinness World Records. He has composed for every Dragon Quest game, including the spin-offs. What especially makes the Dragon Quest IV soundtrack stand out are the little details in the soundtrack that were very rare for a Nintendo soundtrack.

The most notable detail is the crescendo in the battle theme. A crescendo is an indicator to a music performer to make the music gradually louder, or gradually softer. Such techniques were almost impossible to achieve on a Nintendo system. And in a time where ports to more advanced systems would improve the quality of the audio, the crescendo detail is lost in the PlayStation and Nintendo DS ports of Dragon Quest IV.

The second most notable detail is the inclusion of character specific themes. You notice this in each chapter of the game when you're in the games overworld. And in chapter 5, when you've recruited all your allies, the overworld music is determined by which party member you put in your lineup first. Character themes in video games were even rarer than composition techniques like the crescendo.

Innovative details like these on top of a soundtrack that is both catchy, dramatic, and suspenseful, mark for a soundtrack worthy of investment.

Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake (MSX2), composed by the Konami Kukeiha Club

Metal Gear 2 was the second main entry in the Metal Gear series, about Solid Snake's mission to stop a terrorist plot in the millitary nation known as Zanzibar Land. It was a sequel that almost didn't happen, as Hideo Kojima, series creator didn't plan on making anymore Metal Gear games after the first one. It wasn't until after finding out about the game Snake's Revenge from one of that game's developers that he started to formulate his version of a sequel to the first game, which ended up being released a few months after the initial release of Snake's Revenge.

At first glance, it doesn't look like it could be a Metal Gear game that could hold a candle to any of the games in the "Solid" series. However, a lot of the game mechanics many gamers noticed when playing Metal Gear Solid were actually introduced in Metal Gear 2. Smarter enemy AI, multiple ways to avoid the enemy, complex narratives, betrayal, and fourth wall breaking. But the game never received as much attention as the first few Metal Gear Solid games did, until it was included as part of the Metal Gear Solid 3: Subsistence collection.

The style of music is parallel to action/drama style of music that was established in the first Metal Gear soundtrack, and some of the Metal Gear Solid soundtrack. Normally, MSX games had a sound similar to what you would hear in most, if not, all Nintendo games. But Metal Gear 2 manages to

go beyond the typical chip-tune sound. To create a soundtrack that sounded sophisticated for an MSX2 game, a custom sound chip called the Konami SCC was developed by Konami, in conjunction with synthesizer brand Yamaha. It had only been used in two previous games; Nemesis 2, and Snatcher. By inserting the Konami SCC inside the game cartridge, Konami was able to work with extra sound channels that otherwise weren't available in other games.

Some of the music in the soundtrack would be reprised in the VR training disc of the Japanese release, Metal Gear Solid: Integral, released in the states as Metal Gear Solid VR: Missions.

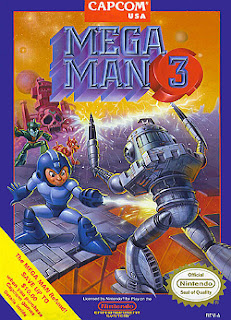

Mega Man 3 (Nintendo), composed by Harumi Fujita and Yasuaki Fujita

After Manami Matsumae composed Mega Man 1, and Takashi Tateishi composed Mega Man 2, the task of composing for a Mega Man game was left to Harumi Fujita. She was only able to finish three pieces before taking a maternity leave. Those three pieces were Needle Man's stage theme, Gemini Man's stage theme, and the staff roll. The rest of the soundtrack was composed by Yasuaki Fujita. Although the two share last names, there is no relation between the two. It was Yasuaki's first Capcom game as a primary composer. He had previously worked on the soundtrack to Final Fight along with various other Capcom composers.

The Mega Man series tends to recycle themes and motifs from previous games. However, none of the music in Mega Man 3 was recycled. All of it was 100% original material. The "Get Weapon" theme from 3 did resurface in future Mega Man games, most notibly appearing as an arrangement in the North American main theme of Mega Man X5.

Mega Man games for the Nintendo games are not only famous for redefining the action platformer genre, and for allowing players to follow a non-linear path to the endgame. The Mega Man games are also highly regarded for their upbeat and catchy soundtracks. 3, in particular, is very consistent in presenting memorable pieces from the title screen sequence all the way to the staff roll.

Misty Blue (PC-88, PC-98), composed by Yuzo Koshiro:

Misty Blue is a first person visual mystery novel. You are musician Kazuya Mizukami, who becomes the prime suspect of a murder after returning to

Japan from studying abroad.

Yuzo Koshiro was chosen to compose for this game. Before this, he was a primary composer for Nihon Falcom. After becoming a freelance composer, he shifted his composition skills to the 16-bit consoles. But he still found time to work on a few PC-Engine games, like Misty Blue. The music in Misty Blue does an excellent job showcasing why Yuzo Koshiro was considered one of the best game composers in the 90s, before composing for games that would ultimately solidify that praise. His influences were primarily what was popular on MTV at the time, and the music of Prince, specifically Prince's contribution to the Tim Burton Batman movie.

With those influences, he was able to craft an upbeat soundtrack blending eurodance, rock, and 80s pop into one game. It's very apropos that this soundtrack sound like the music that was popular back in the day, as the game does involve interacting with many different people in the entertainment industry.

Super Mario World (Super Nintendo), composed by Koji Kondo:

Super Mario World was one of the key launch titles for the Super Nintendo, and arguably the best of Mario's 2D adventures. In this game, Mario has to rescue Princess Peach from Bowser on Dinosaur Land. Here in Dinosaur Land, he is assisted by his newest friend, and Nintendo's newest character, Yoshi. Yes, Mario punches Yoshi, we've known this for a long time.

Koji Kondo, primary Nintendo composer at the time, composed the entire soundtrack using an electronic keyboard. If there is ever an example of how to perfect the variation technique in music composition, it's this game. Most of the themes you hear in this game are variations of one another. The outdoor and indoor athletic themes, ghost house, castle, and underwater themes are all variations of one, single overarching theme. But the variations are done so in a way that they can still be considered catchy, enjoyable, and fitting to the level. Be it a haunting atmosphere, or an underwater waltz, or just your typical athletic theme, you'll feel like you're hearing something fresh every time.

And speaking of Yoshi, anytime you took a ride on Yoshi, bongo drums would be added to the music in real-time. It's little innovations like this, and the way variation was used, that helped make Super Mario World a musical stand-out in the wake of a brand new system. Of course, the pieces that weren't variations of the overall theme deserve praise as well, particularly the final battle theme against Bowser.

Koji Kondo was inspired by hard rock music of the 70s, but hardware limitations prevented him from really showcasing that influence. But the Super Nintendo gave him a chance to show us the kind of rock music that he was capable of, in one of the most dramatic, and one of the most intense battles against the king of all the koopas.

Finally, what made this soundtrack stand out was Kondo's ability to sneak in an easter egg within the soundtrack. If you wait awhile in the Special World map, you'll hear an arrangement of the very theme that made Koji Kondo famous in the 80s. The athletic theme from the very first Super Mario Bros theme.

Super Mario World was a one of a kind soundtrack for its time. A technical innovation, and a worthwhile introduction to the Super Nintendo.

F-Zero (Super Nintendo), composed by Yumiko Kanki and Naoto Ishida

F-Zero was fast paced. F-Zero was exciting. F-Zero was rocking. F-Zero was incredibly fast.

In addition to using F-Zero as an opportunity to showcase its fast paced gaming, and it's mode 7 graphics, F-Zero gave Nintendo the opportunity to showcase a fast paced rock soundtrack performed on the Super Nintendo hardware. First party Nintendo games had primarily light hearted jazz, or

adventurous orchestrated soundtracks. Never an entire soundtrack that would fit the rock genre.

Like Mario, Zelda, and Metroid before, F-Zero's innagural game in the franchise was filled to the brim with iconic pieces. For example, the Mute City theme could arguably be considered F-Zero's main theme. Since Captain Falcon's inclusion in the Smash Bros series, the Mute City theme has become more closely associated with the Captain Falcon character. This makes the Mute City theme more iconic, as at one point in F-Zero's development, Captain Falcon came close to becoming the mascot for the Super Nintendo. But the F-Zero soundtrack was more than just Mute City. For each track you raced on, it was a mood setter. Some of these race tracks were very intense. However, even the most intense tracks didn't require intense music.

And that's one thing that makes the F-Zero music stand out. As intense, and as fast as this game was, the music wasn't required to match that fast paced intensity. The music blended several different elements of rock, and fusion jazz into something that could be considered more pleasant than intense. The other thing that is worthy of mentioning here is the bass throughout. It's hard to hear over the sound effects in the game, but pay attention when you pause the game in specific tracks. You will definitely notice some of the best bass work to help show off the capabilities of the Nintendo S-SMP audio processor. And it's not just one bass either. You get different kinds of bass samples throughout. Acoustic, slap, synth, double...different bass samples to create a kind of rock soundtrack that would not have been possible on other systems at the time.

Startropics (Nintendo), composed by Yoshio Hirai

Startropics was a special kind of game, in the sense that it was devloped by a Japanese staff, featuring director Genyo Takeda who also directed the Nintendo version of Punch-Out. And yet, it was never released in Japan. Startropics is about a young boy named Mike who traverses through different islands and monster infested dungeons in search for his missing uncle. The game played like traditional JRPGs in the overworld, but inside the dungeons, it played more like a graphically enhanced Zelda title.

Yoshio Hirai's composition profile for video games is small, as only two of the three titles he worked on were Startropics games. But it's hard to dispute how fun this soundtrack is. The soundtrack can go from very lively, to very dramatic in mere moments. Traversing through the overworld islands, and the first part of dungeons feels like a fun, tropical escapade. But when you converse with the island locals, find yourself deeper into dungeons, or encounter a boss enemy, the music becomes more intense. What makes the lively music stand out is the bass work. If you listen carefully to the overworld theme, the dungeon theme, the overworld theme while in the submarine, the Miracola theme, and the final dungeon themes back to back, you will hear the same bass riff used each time. It's almost as if the more upbeat pieces were built around this specific bass riff. Rarely do you hear this much effort placed in a large portion of a video game soundtrack, even by today's standards.

Startropics also managed to incorporate music into one of the games puzzles. During chapter 5 of the game, you have to play an organ hitting the notes in a specific pattern. The pattern is told to you by a parrot using solfeggio, the method of education used to teach children about singing in specific pitches. You would recognize solfeggio by its syllables, do re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti, and do. The game required that you learn which notes of the organ matched the solfeggio syllables by ear. It was the simplest way for a Nintendo game to introduce one of the most basic music theory lessons, while simultaniously providing gamers with a difficult puzzle that needed to be solved to advance the story.

Startropics is well known for the puzzle that required you to dip a letter that came with a physical copy of the game in water to find a secret code. As great, and as creative as that was, it shouldn't overshadow the imporant role that music played in Statropics, both in-game, and behind the scenes.

ActRaiser (Super Nintendo), composed by Yuzo Koshiro:

In ActRaiser, you play the role of God, and your main objective is to resurrect the world lost to Satan and his powerful lieutenants. The game is played in two different ways. One is the action style, where you control an animated statue as it destroys the enemies in front of it. The second is

the simulation style, where you control God's faithful angel servent as he rebuilds civilization from the parts of the world cleared by monsters.

This was Yuzo Koshiro's first assignment for the Super Nintendo, and his first job working

with a system that didn't have an FM Synthesizer. Although the Super Nintendo hardware, he found that it was easier to recreate the string sound than on previous systems he had worked with. In the 16-bit era, he has stated that he preferred working on the Sega Genesis. But he still found it relatively

easy to compose the music for ActRaiser by swapping samples from the ROM data, allowing him to only load the parts of the music samples he needed, without having to limit himself to the Super Nintendo's 64KB memory limit, and it's inability to load multiple samples at a time.

Video game music before ActRaiser's initial release did not sound anything like this. This was the closest any game had come to creating that authentic orchestra sound at the time. It even does a good job covering various moods. Relaxing, intense, whimsical, dramatic, suspenseful, mysterious, and everything in between. Only released in the Super Nintendo's second month in Japan, Yuzo Koshiro showcased the potential that the Nintendo S-SMP audio processor was capable of delivering.

The Secret of Monkey Island (floppy disk), composed by Michael Land, and Patrick Mundy

All Guybush Threepwood wanted to be was a pirate. Little did he know that he would have to find burried treasure, successfully steal from the governor's mansion, and excel in insult sword fighting to become a pirate. Not the Pirates of the Carribean kind of pirate, but a very awkawrd yet kind-hearted pirate.

The formula for a classic LucasArts adventure game is this: Witty writting, memorable characters, and a cinematic score that seemed commonplace in LucasArts games, but uncommon in other games, especially console games at the time. The Secret of Monkey Island was the first game to use an in-house composer, Michael Land. Despite this honor, Land found composing for the game difficult. He had the freedom to compose the game how he envisioned it, by incorporating light-hearted Caribbean and reggae music everywhere, even during the most tense situations. But the sound engine he had to work with made it difficult for Land to bring his musical vision to life. So with the help of his friend

Patrick Mundy, the two created a sound engine that he described as "[making] music respond to the unpredictable interactive changes in the game as if the music had been composed with advance knowledge about what was going to happen." This engine would be called iMUSE.

The iMuse sound engine enabled the game to decide which of the music layers would be emphasised over the others in any situation the game presented to the player. Thus, making adding an interactivity element to the games soundtrack. The iMUSE system wouldn't actually be used until the games sequel, LeChuck's Revenge. But the challenges that Land faced when composing for the first Monkey Island helped influence an audio system capable of recognizing which scenarios warrented the most appropriate music tones. As for the game itself, one of the most popular pieces is the main theme. Land states that the music came to him almost immediately while playing on an organ, except for the last few seconds of the theme, which took considerably more effort to write.

The Secret of Monkey Island is a prime example of a game that helped not only define the adventure genre, and writing in video games, but it also helped inspire how music can be used to actually enhance the gaming experience beyond simply adding music to the background and leaving it there.

Turrican (Amiga), composed by Chris Huelsbeck

"Welcome to Turrican."

Preceding the ominous greeting was a soundtrack that was very suitable for a run and gun style game, with inspiration literally drawn from the soundtrack of the original animated Transformers movie, and Manowar. Speaking of Manowar, look up the cover of their album Kings of Metal, and then look up the title screen of Turrican. The metal influence is definitely felt throughout this game. Even in the loading screens, you are given a rockin' track to help ease the waiting period. In Turrican, you are a bio-engineered warrior with the task of liberating the colony of Alterra from rebellious organisms from a corrupt eco-system network known as MORGUL, Multiple Organism Unit Link.

This game was also developed for the Commodore 64, but the C64 version hardly had a soundtrack. Certainly the kind of soundtrack Chris Huelsbeck contributed to the Amiga version of this game. With the kind of metal influence that the soundtrack had, he could have easily given every part of the game a stellar, head banging piece to acompany the game. But he didn't. There are parts of the game where the music actually takes an ominous turn. In certain areas, the music is nothing but isolated winds, creepy clicking sounds, and the only resemblance of music of any kind is a very scattered drum riff. Not many games, especially in the run and gun genre, did this. In this genre, every level had to have music. Music with a real melody. Even the haunting, ominous worlds had to have music acompany them. Turrican and Chris Huelsbeck broke that traditional mold, and added a kind of errie element rarely seen in run and gun games, even today.

Turrican has become one of the more cult classic franchises from the 90s. Arguably, however, the most popular aspect of this game has always been the music. Quintessential for its time, but also a timeless part of video game music history.

No comments:

Post a Comment